In the 1970s, Mexican Mario Molina and American F. Sherwood Rowland began to study the effect of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) on Earth’s atmosphere.

CFCs had been first synthesised just a few decades earlier, and had been widely adopted by many industries. Their low toxicity and low flammability made them ideal for for use in aerosol sprays and as refrigerants. Production grew to exceed a million tonnes a year, and CFCs looked to be yet another incredible human innovation that would drastically improve our lives.

Whilst it seemed clear that CFCs were harmless to humans upon direct contact, we didn’t understand how the large quantities we were releasing would react with the atmosphere. That is the question that Molina and Sherwood sought to answer.

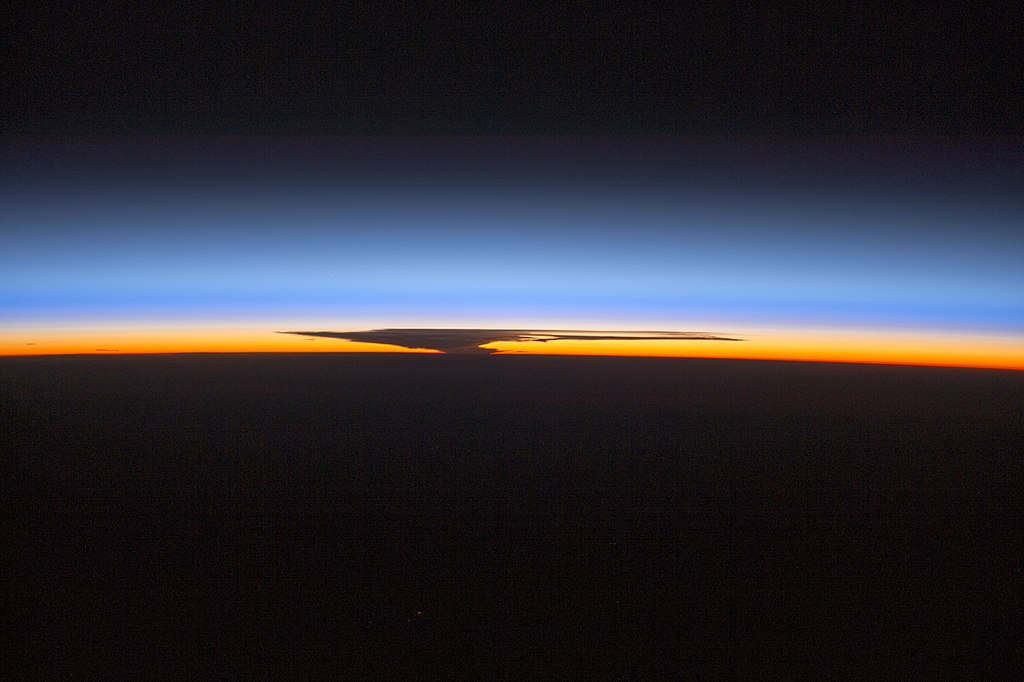

One of the useful properties of CFCs is their low reactivity. However, this means that they don’t break decompose in the lower atmosphere, and instead float up to upper stratosphere, and through the Earth’s ozone layer. The ultraviolet radiation that the CFCs are then exposed to (having previously been protected by the ozone layer) breaks them down and releases their chlorine atoms.

These chlorine atoms are then free to react with the O3 molecules that make up the ozone layer, a reaction which splits the ozone into oxygen and chlorine monoxide, neither of which provide any protection from ultraviolet radiation. The chlorine monoxide can then itself react with the ozone, splitting it into oxygen and another chlorine atom – which will then react with another ozone molecule, releasing chlorine monoxide, and so on.

This chain reaction was theorised by Molina and Rowland to have destructive potential. They predicted a 30-50% depletion of the ozone layer by 2050 if current growth CFC production growth continued (and plateaued in 1990). The huge resulting increase in UV-B radiation reaching Earth’s surface would cause rates of skin cancer and cataracts to skyrocket, and could wreak havoc on ecosystems that have evolved protected from UV for 100s of millions of years.

And so, Molina and Rowland proposed a simple solution to the CFC problem – ban them.

Molina and Rowland’s findings were immediately dismissed by the CFC industry. The chairman of DuPont, one of the world’s leading CFC producers, described the Rowland-Molina ozone depletion hypothesis as “science fiction”, as his company spent millions on newspaper advertisements to defend CFCs.

Despite the forming scientific consensus around the validity of the Rowland-Molina hypothesis, industry denial did not waiver. The reason was clear; regulation to protect humanity from the dangers of CFCs would harm the profits of CFC producers.

A 1979 National Academy of Sciences report suggested we could see a 16.5% loss of ozone, Du Pont responded “No ozone depletion has ever been detected. […] All ozone depletion figures to date are based on a series of uncertain projections.”

Egyptian scientist Mostafa Kamal Tolba had been serving as the director of the United Nations Environment Programme, and was clear in his assessment of the problem to UN delegates. If the present lack of CFC regulation were to continue, the world would be facing ”an environmental catastrophe which will witness devastation as complete, as irreversible, as any nuclear holocaust.”

Others were sceptical about the prospect of international cooperation on this issue, with Daniel arap Moi, the President of Kenya at the time, suggesting there was a lack of political will to act in a united fashion.

Some countries were beginning to heed the warnings of the scientific community and were implementing bans of the use of CFCs in aerosol spray cans. But, when data retrieved from a British Antarctic survey in 1985 revealed a huge hole in the ozone layer, lawmakers understood the need for unilateral action.

Further Antarctic expeditions led by atmospheric chemist Susan Solomon found the rate of ozone depletion to be even worse than predicted by Molina and Rowland.

Tolba was instrumental in bridging the gap between scientists and politicians, and brought about negotiations that eventually led to the Montreal Protocol of 1987.

Incredibly, Du Pont’s science denial continued into the 90s. After the U.S. Senate ratified the Montreal Protocol, Du Pont claimed “At the moment, scientific evidence does not point to the need for dramatic CFC emission reductions.” In 1990, as nations agreed to strengthen the Montreal Protocol, Du Pont CEO Ed Woolard said “In my opinion it has not been proven that CFCs are harmful to the ozone, but there is a fairly good probability, and we have to deal with that.”

Almost 40 later, the Montreal Protocol stands as shining beacon of international coordination. Proof that, when the stakes are high, we can set aside our differences and act in the interests of all. Our world in 2024 has its own problems; the existential risk from artificial general intelligence, the continuing threat of nuclear war, and the dangers posed by unfettered climate change.

These issues, whilst worrying, are solvable. Let us take inspiration from the spirit and drive of the heroes who saved our ozone layer (and 100s of millions of lives) as we strive to accept the reality of problems we must deal with, to stare them in the face, and to act.

Mostafa Kamal Tolba, Mario Molina, Frank Sherwood Rowland are all no longer with us, but they are remembered.

Today, the 16th of September, is the 37th anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. Happy Ozone Day!